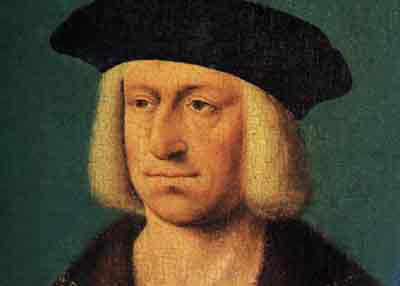

Charles Habsburg was born in Ghent, a region now located in Belgium. His four grandparents, Emperor Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire, Duchess Mary of Burgundy, King Ferdinand II of Aragon, and Queen Isabella I of Castile, carefully planned a dynastic marriage that would result in one extremely profitable heir. Charles was the eldest son of Philip the Handsome and Joanna of Castile, and he therefore inherited ample land throughout Europe. From Duchess Mary of Burgundy, his maternal grandmother, he acquired the remaining land of the Duchy of Burgundy in southern Europe, Flanders in the north (presently known as Belgium and the Netherlands), and some holdings in central Europe.

Emperor

Maximilian I

Duchess Mary

of Burgundy

Queen Isabella

I of Castile

King Ferdinand II

of Aragon

Philip the Handsome

Joanna of Castile

Charles V

King Ferdinand II of Aragon, his maternal grandfather, left him most of the Iberian Peninsula, therefore making him King Carlos I of Spain. Charles also inherited eastern Spain and Aragon’s colonies in the Mediterranean. From Queen Isabella I of Castile, his paternal grandmother, Charles acquired central Spain and Castile’s American colonies. Emperor Maximilian I of the Holy Roman Empire, his paternal grandfather, left him the Austrian crownlands.