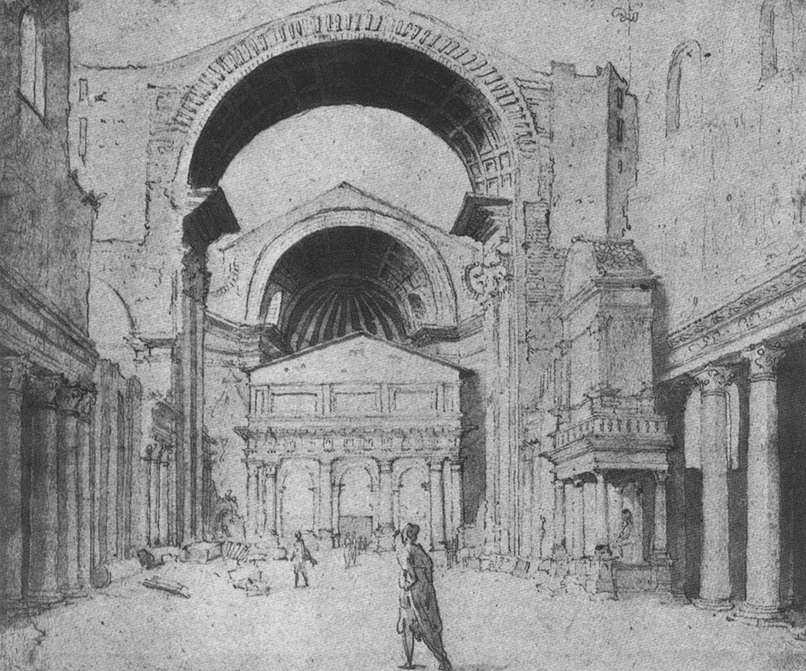

Some idea of how these temporary chapels may have looked comes from a drawing of the temporary tabernacle over the tomb of St. Peter in front of the apse in the Vatican basilica, although the chapels set up in San Petronio were smaller and less monumental.

This drawing also shows that in 1530, St. Peter’s was not the magnificently decorated majestic “queen of basilicas” we see today; it was indeed an ungainly, partly dismantled Constantinian/Early Christian basilica of the fourth century, with an unfinished Renaissance centralized church rising within and around it. The Church of San Petronio itself was still under construction; it had yet to be vaulted and the choir was later extended and enlarged. The unfinished condition of both churches may have made the conceit of San Petronio tranformed into St. Peter’s easier to accept at the time. The wooden platform put up for the occasion in the middle of San Petronio was arranged to make the area in front of the high altar appear sunken, to suggest the sunken crypt-like space in front of the high altar in St. Peter’s. According to Vasari, the nave was lined with wooden Ionic colonnades set up for the coronation. If Vasari was correct, these colonnades would have enhanced the intended transformation of San Petronio into Saint Peter’s, which, as the drawing shows, still had its original Constantinian rows of spolia columns lining the nave. An idea of what such an Ionic colonnade would have looked like can be gained from a Fifth-Century Christian basilica in Rome, Santa Maria Maggiore: